How Do You Solve a Problem Like China’s Public Health Care?

This is the first article in a series about health care reform in China.

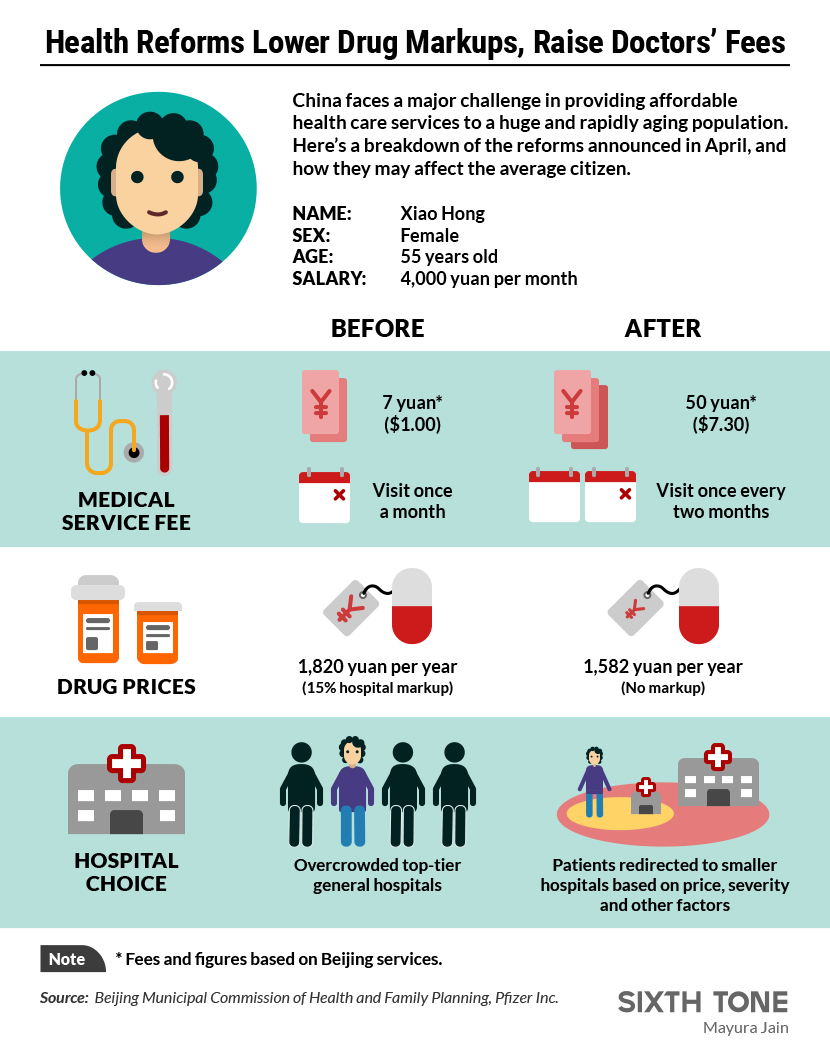

China’s latest round of medical reform, announced in April, aims to address some of the major challenges to providing health care to the world’s most populous nation — especially as economic growth slows.

“The reform has entered the most critical period,” said Zhuang Ning, deputy director of the Department of System Reform at the National Health and Family Planning Commission, in a commentary for Beijing-based newspaper Guangming Daily in May. Zhuang wrote that though the country has already made significant advances in health, further reform is needed to ensure comprehensive and affordable health care access nationwide.

“There is no peace and prosperity without the health of the whole population,” Zhuang stressed.

Overcrowding plagues the country’s public health services, which are typically concentrated in big urban hospitals. Pricing is opaque and inconsistent, as inadequate direct funding from the government forces hospitals to rely on markups on services and medications to generate income. Distrust of doctors is high, due in large part to the public perception that health professionals often take bribes from patients and kickbacks from pharmaceutical companies, resulting in overprescription and other treatment issues. Doctors, too, are increasingly frustrated by overwork and lack of professional flexibility.

Starting in April, a raft of changes came into effect: The price of prescription medication was standardized starting with a few regions, including Shanxi province and Beijing in northern China and Guangdong province in southern China. A new medical service fee was implemented in a pilot program across Beijing, aiming to make pricing more transparent and divert simple cases from top hospitals to community-level institutions. Nationwide, new workplace policies were established to allow doctors from public hospitals more freedom to work at different health care practices, including private hospitals and small medical groups. Reforms have also built alliances among health care providers and regulated the booming online health service industry.

In the past, health care policy has focused on extending medical insurance coverage into rural areas and strengthening service delivery: more doctors, more beds, more funding. Now, the emphasis is on improving quality of care and giving both patients and doctors more choices.

While new policies claim to strive for equal access to quality health care for all, some of the reforms resemble a shift toward market solutions — a user-pays model, which could exacerbate inequality.

According to statistics from the National Health and Family Planning Commission, though the total number of hospitals in China increased between 2014 and 2015, the number of public hospitals actually dropped, while the number of patient visits to these hospitals grew.

Top-level public hospitals, especially those in big cities or provincial capitals, deal with extraordinary pressure: In 2016, China’s largest hospital received close to 20,000 outpatients in one day.

In a bid to guide patients to more appropriate facilities, the country’s health authority has been working to build regional health care alliances, which connect top-tier, second-tier, and community-level health centers through training and advisory partnerships to ensure quality services at each level. By the end of 2016, a total of 205 Chinese cities had established regional health care alliances — accounting for 60 percent of cities, Wang Hesheng, vice minister of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, said at a press conference in April.

Authorities are also overhauling the funding system. Beijing has become one of the first cities in the country to completely remove the markup on drug sales in public hospitals, instead imposing higher medical service fees to subsidize these institutions. The new pricing system aims to give more recognition to doctors’ professionalism, curb overprescription and corruption, and ensure that hospitals operate more sustainably. But to patients, it seems like they’re paying more for appointments — and for some, it might mean visiting doctors less often.

To better retain top talent in hospitals, from the beginning of April, doctors nationwide have been permitted to practice medicine outside the hospitals to which they are contracted. Some will take advantage of the opportunity to test the waters in the private sector. Others are joining together with like-minded peers to form their own private medical groups. Yet some doctors say the policy hasn’t made a difference, as their employers still frown upon those who moonlight at other sites.

Nonetheless, China’s private health care sector is growing. There are now more private hospitals than public in the country, though they are typically smaller. By the end of 2015, private institutions provided more than 1 million hospital beds — 19.4 percent of those available — representing an increase of 161 percent from 2010. The state is promoting commercial health insurance to help alleviate the foreseeable economic burden of caring for its vast, aging population. Beginning July 1, a national policy will give income tax breaks of up to 1,080 yuan (around $160) annually to citizens who purchase commercial medical insurance.

In an in-depth series this week, Sixth Tone looks at the health care reform that has taken place in Beijing, standardizing drug prices and raising treatment fees; the national policy that gives doctors more professional freedom in choosing their workplace; and how doctors in the public system are themselves beginning to embrace entrepreneurship in the private sector.

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

(Header image: A nurse administers intravenous fluids to patients at a hospital in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, Jan. 30, 2014. VCG)